To understand why the banking crisis of 2007 happened and to know why it could happen anytime again (and in all likeliness, given enough time, will happen again), we need to dive into a few basic issues of economics. Like what is money, what is the economy based on in general, finishing with the comparison of inflation/higher prices vs. income.

A good starting point is the question, what money is. Most people are startled when presented with this one, and I suspect most MBA’s don’t know the answer to it. In short, money is debt. It is quite scary that only a small fraction of the general public, and even a small fraction of people who are in one way or the other tied professionally to the banking system are aware of this simple fact. The exact number depends on the country you live in, but the percentage of money being hard cash is less than 5 percent, at best. The usual is more like 2 or 3 percent. The rest is just credit, stored in a computer as numbers in a database of some bank somewhere. So why is money debt? Because every time a bank opens up a credit line, i.e. lends money to a person or company, that money is created. Banks, no matter if owned publicly or privately, are allowed to do so. The bank expects the money to be returned after a given amount of time with an extra on top – the interest.

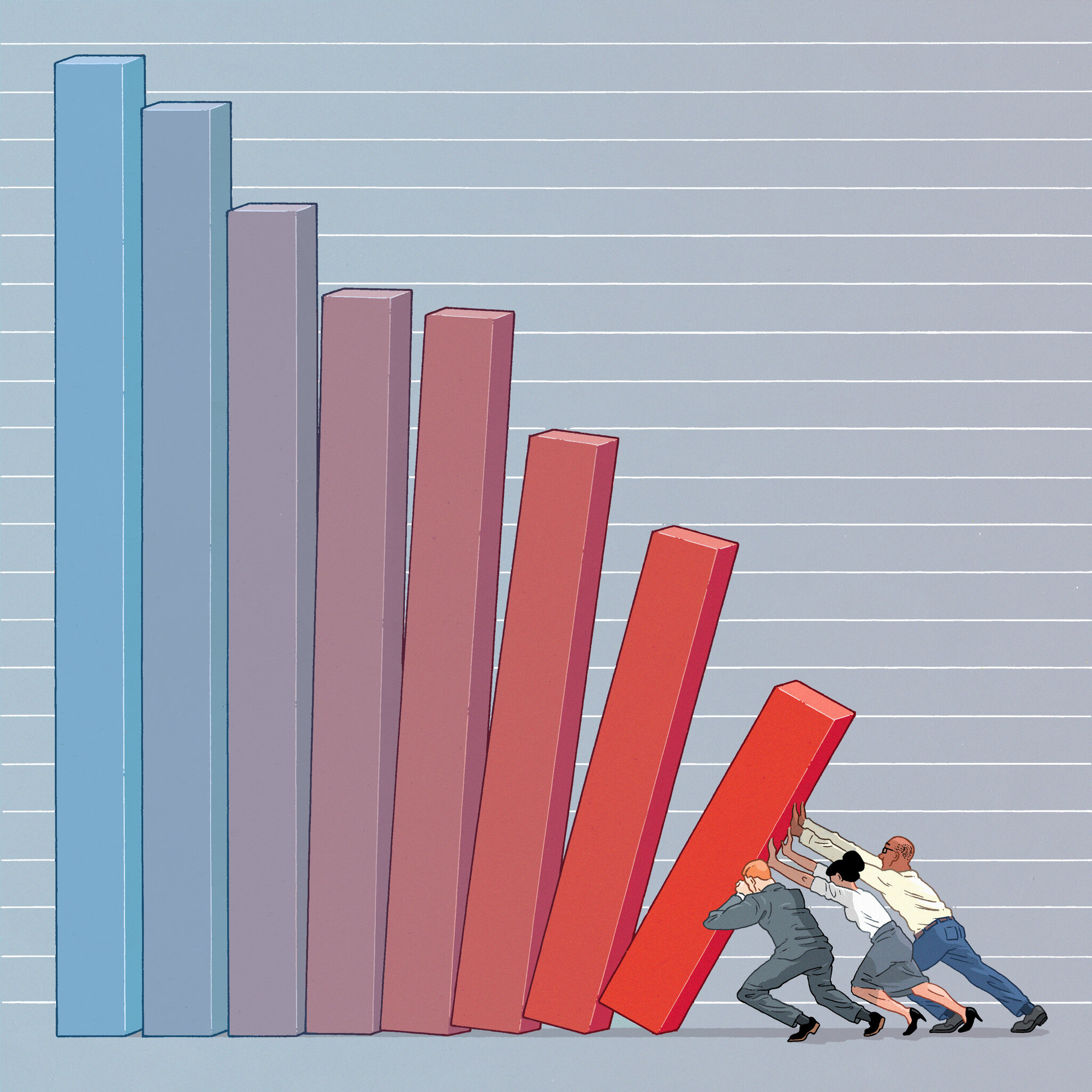

It may sound counterintuitive, but the more debt there is, the better the economy is doing. Because debt usually means growth. In the case of personal debt, the person to receive the money is not likely to just sit on it, but spend it for whatever thing or reason – something that furthers economic activity. In the case of a company, debt is usually created for either starting a business from scratch, or expanding an existing one, which again, is positive for economic activity and growth. In short, the more debt, the better the economy is doing. The problem with this system is: what if too much credit is given, without the receiver ever having the possibility or will to pay it back? Imagine a bank issuing too many, in this sense, faulty credit lines. The money does not return to the bank, and in turn, the bank itself becomes financially unstable and may even go down and perish. But banks – at least the big ones – are so essential to the system, for providing credit to customers, private and corporate ones, that they may not die, because the whole financial system would do go down with them as a result. You see, other banks will notice the bank being tarnished financially, so they will not lend any money to it. If a lot of banks exhibit this kind of behavior, giving out too much credit that can never be repaid, the whole system goes down with them and the trust in money, no matter if cash or credit, is lost. The thing is: banks have a general interest too open up as many credit lines as possible, because that means, by interest, they earn more. So what happened in 2007? Too many (basically all) banks, got greedy and gave out too much debt, that could not be repaid (sometimes even knowingly so) and also, speculated heavily with high-risk financial products. They packaged their faulty credit lines and sold it to one another in whole bundles. Sometimes they mixed good ones with bad ones to make it look better. In 2007, a lot of banks the just wanted to get rid of their bad giving-out-credit-decisions of the past and sold it, or tried to sell it, to other banks – those are the high risk financial products from before. But sooner rather than later the truth came out: too much of the credit lines were ones that would never be repaid, and the trust of banks in one another, essential for the business of lending each other money (which banks do all the time) dwindled down, the stock market went with them, and soon the whole economy was in crisis.

There are no real safeguards in place to keep a crisis like the one in 2007 from happening again. Politics did not learn and did not nearly enough to prevent a crisis like this from ever happening again. In 2007, banks were bailed out, what effectively meant: in the years prior they were allowed to privatize their wins in money. But once they had losses- heavy losses due to massively many faulty credit lines – they were bailed out by the government, i.e. the taxpayers money – so they could effectively socialize their losses. Yes, that’s what banks did and still do: privatize their wins, socialize their losses. If we do not want banks to continue operating like they do, bad business behavior, like speculating recklessly with high-risk financial products, out of greed and negligence of risk, and especially not giving out loans that will never be repaid (which are bundled and sold as financial products), needs to have consequences. Consequences like: the bank dies if too much of things like that happen. But banks may not die. The system depends on them. So how does one resolve this issue? One of the simplest and most effective means is: separate investment banking from credit banking. This is one of the most crucial methods: transform banks into regular businesses. Regular businesses do not get rescued by the state. They go down the river if they do bad business. Changing the banking system in that way simply means, make room for the possibility for a bank to go down and under and not take the whole system with it, like any regular company. This element of prevention is as simple as it would be effective, because no bank could allow its employees to do investments or give out loans that are reckless and carry too much risk any longer.

Most ironically for me personally: this possibly single most important element of prevention, the separation from investment banking and credit banking, separation of the making of money from money business from the lending money out to say, companies to grow – has not been established. It was discussed in the EU-commission, and most if not all countries were in favor of it, but my home country, in the person of Wolfgang Schäuble (former minister of finance in Germany), blocked the proposal.

Let us now turn to question on what the economy is based on: in one word, faith. Without the faith that the other party will honor his or her end of the deal, no economic activity would take place. This is true when you’re buying a sandwich, as much as it is true that cash would have no value but people’s faith in it, that it is something actually valuable. I believe that this is why an idea like an unconditioned income for all people – that is, money the state surrenders monthly to every person, no strings or conditions attached – is such a smart move: it would show that the government believes in you, puts its faith in you. A general unconditional income would be the institutionalization of faith by the state.

So how does one know when there is an economic good phase or a bad one? Essentially, all what economy is, is movement. Movement of things, goods, money, objects, people, even thoughts and ideas that will lead to products. A head banker from the Deutsche Bank once described with a story. A careless person leaves a 100-dollar note on the counter of a hotel. A greedy hotel employee takes it to repay some of his debt. The person who gave him the loan in turn, spends it on some product. The person who sold the product, checks into the hotel, and by accident, leaves a 100-dollar note on the counter. The original person who left the note in the first place returns, and is relieved, that it is still there and takes it back.

The point of the story is: even though there was no harm or foul to anyone, because by sheer luck, the person who left the hundred bucks got it back, a lot of economic activity happened in the meantime. In short, money means movement of objects or products or whatever things, and the more of this activity, the better. Money is just there to make this activity happen. Giving out money, i.e. in the form of loans and credits, is something essentially good. What you can and may not do however is become greedy and lend too much money, which in the banks case means, create too much money.

The next, very simple question we shall tackle is: how is money spent?

Prices of things keep rising, especially housing prices. But salaries have not gone up accordingly in the last few decades. Nobody likes to see his or her standard of living diminished. So what do people do when buying things gets more expensive but you don’t have enough money in your account to keep up? Basically, you have three options:

- Work longer hours (and/or get a higher paying job)

- in the not so distant past (like say, the 1950s): send your wife to go working, too. For nowadays: double income.

- take out a mortgage on your house

Especially the latter happened throughout the US in the years prior to 2007. People wanted to maintain and support a certain level of lifestyle, and sometimes recklessly took out mortgages on their own homes to do so. The banks gave out those loans by large numbers, and bundled them into – seemingly solid – financial products, which in turn they could sell on the market. The rating agencies are as much to blame as the banks themselves, because in the overwhelming majority of cases, they rated these bundles of credits far too good. Trusting the rating of a financial product, banks bought up faulty packages of credit lines, to make money of off them in return. Soon, the market was flooded with faulty bundles of credits, but as long as the system remained stable, banks continued with this kind of behavior, out of greed, negligence of risk and recklessness. They wanted their products which were sold and bought to be better – much better – than they were in reality, out of the simple reason to make more money. So they kept issuing faulty credit lines, kept buying bad credit bundles, until the truth finally came out and the whole system collapsed.

Did they learn their lesson? In short: no. In fact, they learned the complete opposite: if things go wrong, the state is there to bail them out. It is outrageous as it is sad for the common man trying to make a living. But it is still the way the system is and is working, up until today.